The inner meaning of the oil rout (and the prospects for stability carnage in the Middle East)

Conflicts Forum Weekly Comment, 22 January 2016

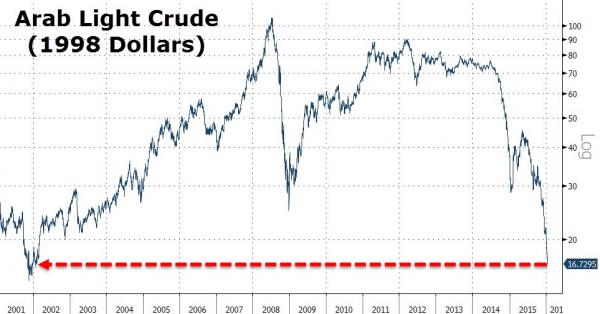

First of all, it (the oil rout) is worse than generally supposed:

Source:Â ZerohegdeÂ

Adjusted for inflation, Saudi Arab Light is trading at less than $17 a barrel. Raul Meijer, a respected commentator, sums up the consequences succinctly:

“The consequences of all this will be felt all over the world, and for a long time to come. All of our economic systems run on oil, so many jobs are related to it, in so many ‘fields’ in the economy… It’ll be a disaster of biblical proportions, like a swarm of locusts that leaves precious little behind. Squeeze oil and you squeeze the entire economic system. That’s what all the analysts advocating ‘low oil prices are great for the economy’ missed (many still do).

Entire nations will undergo drastic changes in leadership and prosperity … But more than that, Middle East nations rely entirely on oil, a dependency that won’t allow for many of their rulers to remain in office. Same goes for all OPEC nations, and many non-OPEC producers.

We can argue that a war of some kind or another can be the black swan that sets prices ‘straight’, but black swans are supposed to be the things you can’t see coming, and Middle East warfare for obvious reasons doesn’t even qualify for that definition. The world is full of nations and rulers that are fighting for bare survival. And things like that don’t play out on a short term basis. For that reason alone, though there are many others as well, oil prices will remain under pressure for now.â€

Secondly, ‘demand’ for crude will not be resuming soon: David Stockman notes: “Almost all of the increase in global oil demand since the 2008 crisis has been in China and its caravan of EM suppliers and fellow travelers. Total global demand in 2015, in fact, averaged about 92.6 mb/d per day (liquids basis) – up nearly 7.0 mb/d since 2008. But 4.0 mb/d of that growth was attributable to China, and another 6.0 mb/d to Brazil, Korea, the petro-states and the balance of the EM economies. By contrast, oil demand in the US, Western Europe and Japan is actually down by about 3.0 mb/d since the 2008 peak, as shown below”:

“Now here’s the thingâ€, continues Stockman: “While the red line above representing the Red Ponzi and its supply chain looks like it’s still slightly rising, it’s actually in the process of heading sharply southward. That means that in the period ahead, demand will be falling all across the planet on a sustained basis for the first time in modern history.â€

Why the New World demand is tailing-off is now quite obvious — China: “It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to figure out the growth in old China for the past year or so has been somewhere around zero — it’s nothing like 6.8%,†Donald Straszheim, head of China research at Evercore IPI complains, explaining that the ‘new’ China of services and consumer spending is tough to measure in the absence of robust data from the private sectorâ€. Mainstream financial commentators however suggest thatthe turmoil in China is but a temporary pause due to the commodity plunge and the EM slowdown, and that this is all just a matter of ‘transition’.

Maybe – but as Martin Wolf notes in the Financial Times: “It is unclear how and whether the transition to a more balanced [Chinese] economy is to be madeâ€. Again, some people focus on the transition from manufacturing to services. This does seem to be going quite well: according to Chinese data, industry grew at an annual rate of just 6% in the first three quarters of 2015, while services grew 8.4%. However, a large part of this apparent success is due to growth of income from financial services. Just as was the case in the West, before the crisis, this is as much a symptom of credit growth as of a transition to a more balanced ‘new normal’.â€

It is perhaps simplistic to think of ‘transition’ in China as simply about the state’s deft redirection of some of these fungible units of demand from the fixed asset sector to consumption and services. In any event, China’s exploitation of cheap crude, by easing rules to allow private refiners to import crude and by boosting shipments to fill emergency stockpiles, seems to be over. Daily rates for benchmark Saudi Arabia-Japan VLCC cargoes (i.e. tanker charters) have crashed 53% in the past year to $50,955 (as it appears China’s record crude imports have ceased).

When then, as all ask, will the ‘recovery’ occur, and the oil price rise? What does the oil price rout mean? Well perhaps it is not just signalling the end to some commodity super cycle, but rather to something more profound. In brief, that trying to kick-start any economy by creating ever more liquidity (QE) and zero interest rates eventually will hit the brick wall of diminishing returns. As one former US Director of the Office of Budget notes, “you can borrow your way to a higher GDP print, as the US did through an explosion of household borrowing in the 20-years prior to the 2008 crisis, or as China and its EM supply convoy did in the business sector during the last seven years, [but] that only pulls activity forward in time.â€Â “At the towering levels of debt which exist in the world today, however, borrowing does not create new wealth; it only mortgages future income.â€

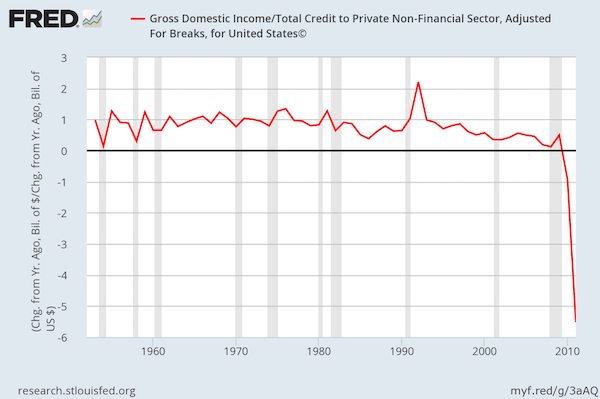

This chart below deals with the productivity or ‘growth’ gained by each incremental dollar of (private) debt incurred:

Source: Automatic Earth

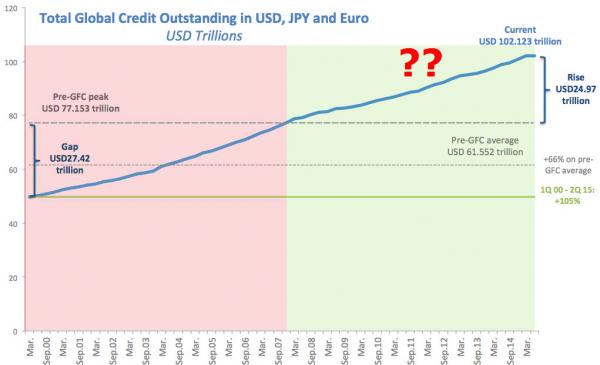

More debt brought diminishing returns in terms of GDP growth: But in spite of the financial crisis of 2007/8, there was no debt reduction – no de-leveraging of this growing overhang of debt – but rather the reverse: it just went on climbing: What happens in these circumstances is that there are massive dead-weight losses in terms of productive assets that simply have become uneconomic, but which march on – thanks to virtually cost free, near zero-rate, financing.

Source:Â Automatic EarthÂ

Source:Â Automatic EarthÂ

Â

But all this extra credit created has produced less and less economic ‘growth’. It has taken more and more dollars of debt to produce just one dollar of ‘growth’ (see here). “Twenty years of rampant global credit growth and 7-years of massive financial repression by the central banks after the 2008 crisis have created a wholly new condition: Namely, there is so much excess, and uneconomic capacity, that it will take years of operation at variable cost to absorb it, or cause it to be eventually abandoned. That means this time there will be no V-shaped recovery of asset values.They are down for the count.†(David Stockman).

The chairman of the OECD’s Review Committee, and former chief economist of the Bank for International Settlements (the Central Bankers’ Central Bank), William White, said in an interviewwith the Daily Telegraph’s Ambrose Evans-Pritchard: “The situation [today] is worse than it was in 2007. Our macroeconomic ammunition [that is QE and zero interest rates] to fight downturns, is essentially all used upâ€:

“Debts have continued to build up over the last eight years and they have reached such levels in every part of the world that they have become a potent cause for mischief. It will become obvious in the next recession that many of these debts will never be serviced or repaid, and this will be uncomfortable for a lot of people who think they own assets that are worth something. The only question is whether we are able to look reality in the eye and face what is coming in an orderly fashion, or whether it will be disorderly. Debt jubilees have been going on for 5,000 years, as far back as the Sumerians.

Stimulus from quantitative easing and zero rates by the big central banks after the Lehman crisis leaked out across east Asia and emerging markets, stoking credit bubbles and a surge in dollar borrowing that was hard to control in a world of free capital flows. The result is that these countries have now been drawn into the morass as well. Combined public and private debt has surged to all-time highs to 185pc of GDP in emerging markets and to 265pc of GDP in the OECD club, both up by 35 percentage points since the top of the last credit cycle in 2007. Emerging markets were part of the solution after the Lehman crisis. Now they are part of the problem too.â€

[Full interview:Â http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/financetopics/davos/12108569/World-faces-wave-of-epic-debt-defaults-fears-central-bank-veteran.html]

In sum, William White is saying that there is such a thing as a collective balance sheet and that it can get used up. Moreover, when that happens there is no more effective ‘stimulus’ to be had — it just results in central banks pushing on a string.

Mr White, who also chief author of G30’s recent report on the post-crisis future of central banking, warns that it is impossible know what the trigger will be for the next crisis since the global system has lost its anchor and is inherently prone to breakdown. A Chinese devaluation clearly has the potential to metastasize, cautions Mr White: “Every major country is engaged in currency wars even though they insist that QE has nothing to do with competitive depreciation. They have all been playing the game, except for China – so far – and it is a zero-sum game. China could really up the ante.”

Mr White said QE and easy money policies by the US Federal Reserve and its peers have had the effect of bringing spending forward from the future in what is known as “inter-temporal smoothing”. It becomes a toxic addiction over time and ultimately loses traction, White explains [i.e. does not lead to GDP growth]. In the end, the future catches up with you: “By definition, this means you cannot spend the money tomorrowâ€. “A reflex of “asymmetry” began when the Fed injected too much stimulus to prevent a purge after the 1987 crash. The authorities have since allowed each boom to run its course – thinking they could safely clean up later – while responding to each shock with alacrity. The Bank for International Settlements critique [the critique by the very club of Central Bankers] is that this has led to a perpetual easing bias, with interest rates falling ever further, below their ‘Wicksellian natural rate’ with each credit cycle”.

“It was always dangerous to rely on central banks to sort out a solvency problem … It is a recipe for disorder, and now we are hitting the limit”, Mr White suggests. The error was compounded in the 1990s when China and eastern Europe suddenly joined the global economy, flooding the world with cheap exports in a ‘positive supply shock’ [i.e. consumers, whose real incomes were falling, were able to continue consuming]. [But these] falling prices of manufactured goods however masked the rampant asset inflation that was building up: “Policy makers were seduced into inaction by a set of comforting beliefs, all of which we now see were false. They believed that if inflation was under control, all was well,” Mr White warned.

“In retrospect, central banks should have let the benign deflation of this (temporary) phase of globalisation run its course. By stoking debt bubbles, they have instead incubated what may prove to be a more malign variant, a classic 1930s-style “Fisherite” debt-deflationâ€. Mr White said the Fed is now in a horrible quandary as it tries to extract itself from QE and right the ship again. “It is a debt trap. Things are so bad that there is no right answer. If they raise [interest] rates it’ll be nasty. If they don’t raise rates, it just makes matters worse,” he explained. “There is no easy way out of this tangle”, writes Ambrose Evans-Pritchard: “But Mr White said it would be a good start for governments to stop depending on central banks to do their dirty work. They should return to fiscal primacy – call it Keynesian, if you wish – and launch an investment blitz on infrastructure that pays for itself through higher growthâ€. White concluded: “It was always dangerous to rely on central banks to sort out a solvency problem when all they can do is tackle liquidity problems. It is a recipe for disorder, and now we are hitting the limit”.

What has this to do with Middle East policy? Well … everything. The EU is on the verge of throwing money, weapons and perhaps troops at the problem of instability in North Africa and the Middle East – in the hope of stemming a tsunami of refugees hitting Europe this summer, and throwing EU politics into a further spasm of internecine warfare.

But if European policy-makers assimilate the implications of what Mr White – a Central Bankers’ Central Banker and a consummate insider – is saying, they will understand that throwing money and weapons into the type of instability Mr White and Mr Meijer are predicting will do nothing to contain the economic/financial crisis that is likely to strike the MENA region. It will only serve to make it more combustible. Ultimately the debt will – and must – come down and economies must be de-leveraged (reducing debt that is levered upon other debt), but the process is likely to be traumatic — it will entail yet more regional political upheaval and increased refugee flight.

The ‘problem’ here is not the drop in the price of oil per se, nor even a forced Chinese devaluation of the Yuan (were that to happen). These are both but symptoms of a far deeper trauma. A devaluation of the Yuan might well be the trigger for the present financial crisis to metastasize into something graver, but the economic and political instability (and deaths) that it will ensue are entirely down to the wrong-headedness and myopia of this unprecedented attempt by Central Bankers, egged on by politicians, to solve a solvency problem by hosing it down with liquidity.

Â